Another Freedom Cut Short

BAGHDAD -- The cleric's young men fanned out across the neighborhood, moving from shop to shop, posting the new religious decrees.

BAGHDAD -- The cleric's young men fanned out across the neighborhood, moving from shop to shop, posting the new religious decrees.Printed neatly on white-and-green fliers, the edicts banned vices like "music-filled parties and all kinds of singing." They proscribed celebratory gunfire at weddings and "the gathering of young men" in front of markets and girls' schools. Also forbidden were the "selling of liquor and narcotic drugs" and "wearing improper Western clothes."

But at the bottom of the list of prohibitions was a single command. Scrawled in green ink, it read simply: "Cut hair."

"I feel powerless," lamented Moataz Hussein, 22, a wiry, soft-voiced teacher seated in a hair salon on the main road of the Tobji neighborhood on Sunday. His long, stylish black hair was now a recent memory. "They are controlling my life."

Amid the sectarian strife plaguing Baghdad, a wave of religious fundamentalism is curbing personal freedoms and reshaping the daily lives of Iraqis who have long enjoyed one of the most liberal lifestyles in the Arab world. The measures speak to a central question dangling over the future of Iraq: Can it remain a secular nation at a time when religion is exerting a powerful influence on every aspect of life, from politics to the mundane elements of society?

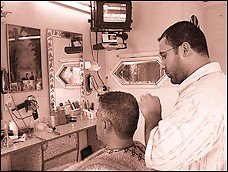

Consider the barbers of Baghdad. Sunni Muslim insurgents and Shiite Muslim extremists have imposed their own sets of rules for the cutting of hair. In recent months, barbers have been killed, threatened or forced to close their shops after being accused of giving haircuts that were considered un-Islamic or too Western.

The new decrees in Tobji, posted last week, came from a little-known council created by the local office of Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr. It is called the Committee for Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, a title derived from a verse in the Koran.

Inside the hair salon, the flier was posted on a cream-colored wall next to a mirror, visible to every customer. The image of Sadr's father, Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr, a revered ayatollah, who was assassinated in 1999, is emblazoned on the flier, giving it the force of law.

It was signed "The Sadr Martyrs Office" and ended with a warning: "Those who do not comply with these rules will be held accountable."

Read the rest at the Washington Post

<< Home